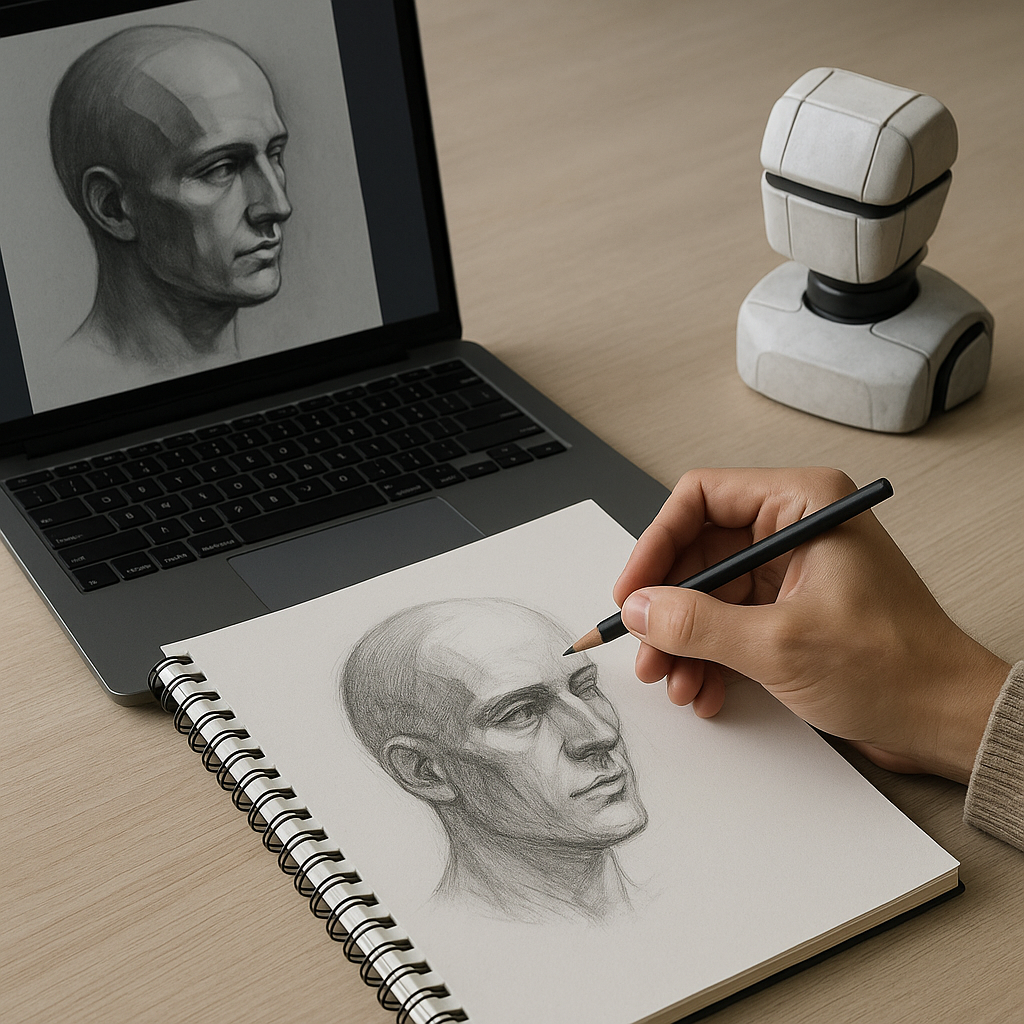

AI’s creative outputs are illusions without human intention

The study claims that creativity cannot exist without intention. Cibotaru explains that human-created works invite interpretation because they are perceived as expressions of personal experience and deliberate choice. By contrast, machine outputs, no matter how complex, are products of code, randomness, or pattern recognition.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has long been hailed as a new frontier for artistic and scientific creation, but a recent academic study warns that true creativity might still be out of reach for machines. The research, titled "Is There Computational Creativity?", published in AI & Society, critically examines whether artificially generated works, from poetry to visual art, can genuinely be described as creative, or if they simply mimic human imagination.

The study's author, Veronica Cibotaru of the University of Tübingen, argues that while artificial intelligence can produce surprising and even valuable outputs, it lacks one essential component that defines human creativity - intention. Her analysis suggests that creative expression requires not only technical capability but also the presence of purpose, awareness, and emotional experience, qualities no algorithm currently possesses.

Rethinking the meaning of creativity in the age of AI

Based on the work of British cognitive scientist Margaret Boden, the author explains two key forms of creativity: psychological (P-creativity), which reflects individual originality, and historical (H-creativity), which reshapes entire cultural or intellectual traditions.

According to Cibotaru, computers can fit both categories in a limited sense. Algorithms can produce original outcomes within defined boundaries (P-creativity) and can even contribute novel works to human history (H-creativity). However, she stresses that these achievements lack the critical element of intentional creation. In her analysis, creativity must go beyond the mechanical combination of ideas, it must express meaning that arises from lived experience and conscious purpose.

The paper argues that while AI-generated poems, images, or music may surprise audiences or carry emotional resonance, this reaction often stems from human interpretation rather than from any intrinsic creative process within the machine. Once observers learn that the work originates from an algorithm without consciousness or volition, their perception of creativity tends to shift.

The missing ingredient: Creative intention and human interpretation

The study claims that creativity cannot exist without intention. Cibotaru explains that human-created works invite interpretation because they are perceived as expressions of personal experience and deliberate choice. By contrast, machine outputs, no matter how complex, are products of code, randomness, or pattern recognition.

The author shows this through examples where AI-generated texts or images can evoke meaning or beauty. Viewers often interpret such pieces as creative until they become aware of the lack of an author behind them. This awareness, Cibotaru argues, breaks the illusion of creativity and highlights the difference between genuine artistic purpose and algorithmic output.

The study also explores how human creators working under rigid constraints, such as writers from the OuLiPo literary movement, still convey intention through their adherence to rules. Their mechanical process is guided by meaning and self-expression, something current AI systems cannot replicate.

The absence of intention, Cibotaru suggests, marks a defining boundary between creativity and automation. Without volition or emotional grounding, artificial systems remain capable of producing only the appearance of creativity, not its essence.

From automation to collaboration: Toward human–AI co-creativity

Despite her critique, Cibotaru does not dismiss the potential of computational creativity altogether. Instead, she proposes four strategies for maintaining its conceptual relevance in the era of generative AI.

The first involves recognizing AI as a less radical form of creativity, capable of generating surprising or valuable outcomes but lacking full creative status. The second approach, advanced by some researchers, suggests attributing limited intentionality to AI systems like DARCI, which can generate visual metaphors and thematic art. While these programs demonstrate goal-oriented behavior, Cibotaru maintains that they still fall short of true creative intention, as they lack consciousness and personal experience.

A third perspective places AI firmly within a human-centered creative ecosystem. Here, machines act as tools that enhance or inspire human creativity. For example, a generative model might produce text or images that humans reinterpret or refine into meaningful works. This approach positions AI as a catalyst for human imagination rather than as an autonomous creator.

However, Cibotaru finds the most compelling solution in the idea of co-creativity - a partnership between humans and intelligent systems. In this framework, AI does not merely assist but actively collaborates with human creators, contributing to the creative process as a genuine partner. This interpretation allows AI to participate in the generation of new ideas while acknowledging that human intention and judgment remain central.

The study cites emerging views that define such systems as creative partners rather than passive tools. This relationship preserves human agency while expanding the creative landscape to include computational collaboration.

The future of creativity: Can AI be a subject?

Lastly, the author raises a provocative question: if machines can be considered creative partners, should they also be recognized as creative subjects?

Acknowledging that current AI lacks consciousness and volition, she argues that answering this question may require rethinking the very concept of subjectivity. Some philosophical perspectives suggest expanding the definition of "subject" to include artificial agents capable of goal-oriented behavior. Others advocate separating creativity from subjectivity altogether, allowing creativity to be defined by process and outcome rather than by the nature of the creator.

Such a shift, she warns, would mark a profound change in how society understands art, authorship, and intellectual responsibility. It would also carry ethical and legal implications, from questions of ownership to accountability in creative industries increasingly shaped by automation.

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse